home > projects and works > fake 2005 > the book - contents

- - - <exhibition>

The Family Archive. Transfer Mode: Buffered Memory/C

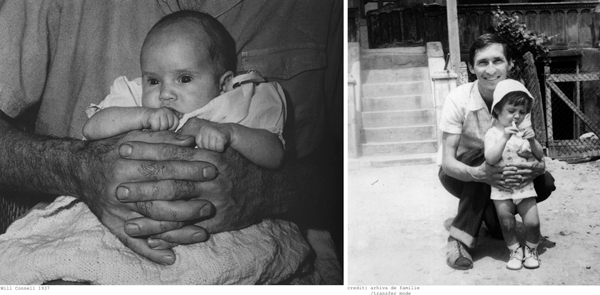

Transfer mode: Buffered Memory/C is the scanner interface that I used one year ago to scan the photographs from the family archive. Once transferred on a digital medium, the scanned photographs develop a clear and well defined aesthetics. The suddenness (intensity) with which they revealed themselves as exhibit items made me consider necessary to store (archive) them together thus giving them a specific identity. My parents did not remember where they kept all these photographs. Every time I wanted to use them in various projects, I was stunned by this absolute forgetfulness, almost indifference... I thought then that the bringing those together on an accessible medium would made it easier to visualise them. Only later did I realise that it was not a question of difficult access but rather an option determined by my parents’ adjustment to the new social reality they were living.

There is a certain amnesia among ordinary people relating to period before ’89.This is partly justified by the major rift that happened then but also by the fact that everybody tried to “re-create” themselves in one way or another. This type of amnesia pertains to the fact that all these people suffered an emotional trauma, a sort of collective guilt with which they have to live and accept. I feel that in order to heal this trauma one has to go back in one’s mind to the exact moments that one is trying to forget. Healing comes with acknowledgment and acceptance. Once acknowledged these moments, the guilt can then be transferred which will resolve the emotional blockage. The family photographs gathered in the project Transfer mode/Buffered Memory/C lay forgotten in every house, blocked by this “effect of the cause”. They are blocked by the sheer will to forget them. This blockage coincides though with my personal history. Every time I try to re-constitute my own journey, I come across this blockage and I feel somehow that my limits have been set externally. If my parents ignoring these images, as far as I am concerned I enjoy looking at these photographs as intensely as I did it as a child.

I was not even 10 years old when, together with other children, we were meeting and surfing the family photographs. The succession of these, image by image, was creating, in actual fact, a “moving image”, a movie. The photos represented the main frames of the film. These were actually the moments/accidents significant from the perspective of a family history. Their significance is different from that that a professional photographer would give when construing an image. The owners of these family photos are at the same time the authors and the actors of the moments they immortalised. This is why they posses an overwhelming documentary strength.

Transferred Mode/Buffered Memory/C is a project that investigates the amateur photography as a ready-made object. This cuts and brings forth a fragment of reality, be it a moment, a thing or a situation, that will then become fixated in the photograph “exactly” as it revealed itself at that time. The attitude of the amateur photographer in face of the “real” is that of a ready-made oriented vector. The composition of the photograph is there to be immortalised. The moment is ready-made. The photographer is taking it as it as, similarly to any objet-trouve, a ready-made. The amateur photography, that from any family archive, is integrating all these ready-mades, hence its documentary character.

transfer mode

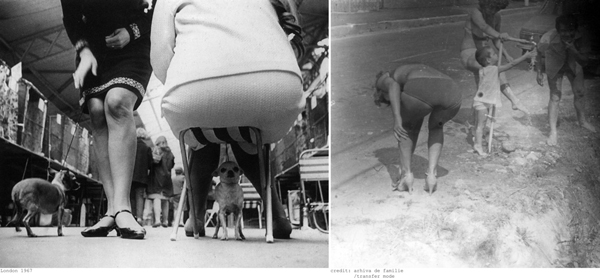

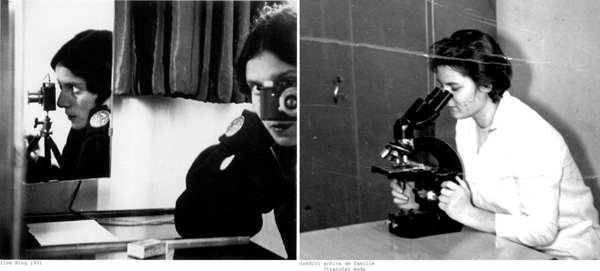

A photograph made by an amateur seduces by accident. These two images illustrate an example situation. It seduces by the strength of the accident. It cuts sharply; it detaches a reality that, by its unexpectedness can stand as a symbol. In actual fact, in this photograph we witness a complete detachment from meaning. The two images speak of the women status at the time when the photo was taken. One cannot sense the true reality of the time covered by this forceful pose. It is striking how naturally the women in these two images stands in the middle of the group of men dressed in military uniforms. If group photography is a frequently used photographic formula for those times, the juxtaposition of women/men in uniform is nevertheless somewhat strange. When contemplating this image one can un-knot numerous forms of interpretation. What was the status of women in a society with strong military flavour? When looking at that image, the characters in the photo can probably remember the moment of its making, and this can be one of strong emotional charge. Twenty odd years later this image is perceived rather differently by somebody of an age similar to that of the people in the photograph. The image bears the inevitable marks of the then social context. The central character may be juxtaposed to the various testimonies from those times “Abortion – abortion was made by anybody by themselves…it was not like today, there were four children to be made…until the age of forty, or even over forty. Abortion was forbidden…so that many children could be born, to raise the population. It was the law, it was the Decree against abortion.”, “it was compulsory to have four children – and maybe this was not what you wanted, maybe the child had no future. And then you used all the available means...the abortions were made by the mid-wife, women from the country that knew how “to pull”. They were pushing your abdomen down, they were grasping your womb from the inside and they were pulling the foetus from its placenta, whatever was there. If you did not lose the baby, you were going to the hospital”. Decretel – the children born in 1968 the year is the connection between the image and the social reality contemporary to that image). That’s because the decree against abortion came out in ’67. That was the first generation of decretei.”[1] The actors of the two photographs were the witnesses and the subjects of that bloody reality. It becomes understandable why amnesia surfaces when you are faced with the prospect of looking again at those photographs-exhibit. It is as if one goes back to the murder scene[2], understood as collective guilt.

The whole archive contains a multitude of such accidents of meaning.

There are things that we completely forget and others we only think we have forgotten. Temporarily forgotten, those things can become available at any time. The archive-photograph as a ready-made object is the photo found in one’s home, saved as a family archive, taking ’89 as the time of reference. When you press delete, the information reaches recycle-bin. The difference between the memory as archive and memory as forgetting is only a matter of option in theory at least. Are you sure you want to press delete? Then empty recycle-bin!

How to bring forth things you have forgotten? What stimuli need to be activated? Ready-made photograph is one of the options. This can be taken as a stimulus. “the thing becomes unconscious sign and the sign becomes unconscious thing”.[3]

Of all the ready-mades pertaining to a specific time-segment, the photography contains information with a strong revealing potential. The frozen moment becomes a signal, and the signal, as an image, re-activates unconsciously the situation which is then re-lived physically and emotionally.

Hope and Nostalgy

The author’s intention for this project is turned towards the childhood of photography as a history of image in the 20th century and the personal childhood as an acquired history through the photographs of the family archive[4]. Both histories are ready-made.

In the 19 sets of relations in this project, the imperfections of the composition and the production of the amateur photographs make them more authentic. The fact that the photos in the Transfer mode. Buffered Memory/c are somewhat altered, discoloured and dirty as well as less thought compositionally and less professional when compared when compared with the professional quality of printing of their western counterparts, gives to the former a sort of superiority, an aura exactly because of those faults. This aura represents a here and a now of the image. The photographs in the family archive become exhibits of the historical evolution of a society and acquire a hidden political meaning.[5]

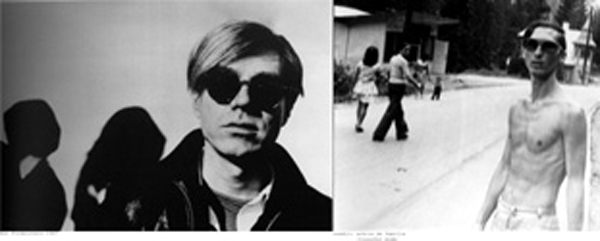

There is an obvious difference of intentionality (or lack of it) between an amateur and a professional photographer. In order to eliminate this difference of intentionality I have used the digital medium. Transferred onto digital format, the difference of perception by equalising the media makes it easier to concentrate on the importance of the content. In this case, the digital support revealing the idea behaves as the verni of the old ones. By digitally vernisare both types of photographs utilised in this project gain unity of texture and their composition can be easily analyzed. The documented type of information becomes a primary factor of perception when analyzing the images.

The unitary aesthetics of the images in the family archive is obtained again by utilising the digital verni. In fact the type of distance that the digital support interposes between the receptor and the photographs equalizes the perception and thus the final processing of the photographs, even if extremely different in physical support, becomes unitary. By using the digital verni, the archive receives a coherent aesthetics.

The unitary aesthetics of the images in the family archive is obtained again by utilising the digital verni. In fact the type of distance that the digital support interposes between the receptor and the photographs equalizes the perception and thus the final processing of the photographs, even if extremely different in physical support, becomes unitary. By using the digital verni, the archive receives a coherent aesthetics.

If we take the photographs to be but a keeper of document-witness for a specific period of time, then the fact that this photograph is an amateur one, unprofessional, does not make it less of a document then the professional one, hence publishable in a family album. The force of document is in both cases at least comparable. In fact, the quality of document as well as the digital support forces them in an equal measure to communicate at their maximum the contained information-document.

Hope & Nostalgy develops a polar attitude when relating to memory. Similarly to the word “before” which in Romanian has two meanings; that of “ahead” i.e. in the future, hope, as well as that of “before” i.e. in the past, nostalgia, the project parallels two types of photography. The genuine amateur photography and the so-called artistic photography. Both types of photography are presented as ready made. Irrespective of the nature of photography, be it amateur (family archive from the East/ nostalgia/ anonymous photography) or be it intentionally artistic (photography albums from the West/ hope/ photography with identity) the only thing transpiring beyond their materiality is the information with the quality of document. They become exhibits of that time. The expressivity of the two types of images transcends time (hope) and become of time (nostalgia).

Notes

[1] LXXX, Anii ’80 si bucurestenii, marturii orale, Ed. Paideia, Colectia Stiinte Sociale, Bucuresti 2003.

[2] Walter Benjamin, Opera de artă în epoca reproducerii mecanice, Iluminări, ed. Idea, Cluj, 2002, p. 115.

[3] Boris Groys, Über das Neue. Versuch einer Kulturökonomie, Despre nou, ed. Idea, Cluj, 2003.

[4] Arthur Danto: “Stilul este felul în care omul se orientează după toate cele învăţate şi dobândite de el”. (Boris Groys, Despre nou, ed Idea, Cluj, 2003), p. 79.

[5] Walter Benjamin, Opera de artă în epoca reproducerii mecanice, Iluminări, ed. Idea, Cluj, 2002.